December 2, 2020

Registered Nurse Deb Greeno fires up her home laptop to stem the spread of COVID-19 as a contact tracer for Alberta Health Services. Photo supplied.

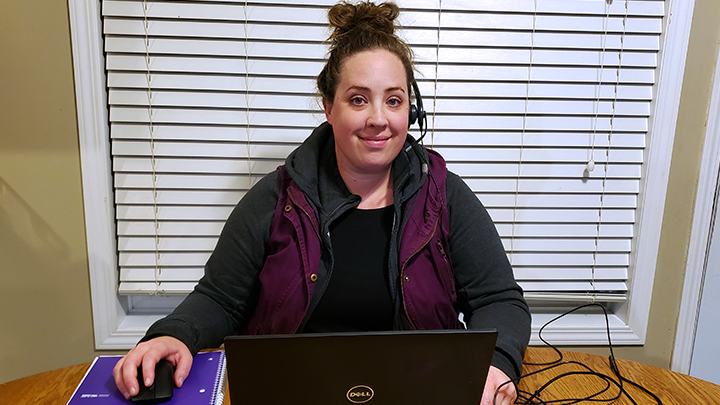

Registered Nurse Kadi Lavorato puts in long hours to battle the pandemic as a contact tracer for AHS in Lethbridge. Photo supplied.

Story by Sherri Gallant

It all happened so fast. In mid-March, at a regular meeting of Public Health staff, almost every registered nurse in attendance for Communicable Disease Control (CDC) was pulled from their regular duties. Their new mission? To work as COVID-19 contact tracers, effective immediately.

Such a challenge is just part of the job description for public health nurses like Kadi Lavorato and Deb Greeno, members of the South Zone team. They’re both seasoned quick-change artists, having navigated outbreaks, natural disasters and more. They’re among more than 800 contact tracers in Alberta whose work is an essential part of containing the spread.

“I think it was March 16 or 17 when cases started to increase,” says Greeno, who divides her workdays from home as well as the local Community Health site. “We would come in at 7:30 in the morning, work sometimes until 9 or 10 p.m., just trying to stay on top with case investigation and contact tracing. Honestly, you didn't eat. The sun would come up and go down. You didn't even notice, because you're kind of hunkered down in the trench looking at your screen, just calling people.”

This fall, Lavorato — who’s working from home on quarantine — has been getting an up-close look at what her patients have been dealing with. Her husband and one of their three sons were exposed to the virus through contact with a hockey team. Only their son tested positive, but all became symptomatic and were deemed probable cases.

Even with her whole family in isolation, Lavorato continues to work, moving her laptop from the kitchen table to the garage to wherever she can find a quiet spot. “Right now,” she says, “I’m working on an upside-down laundry basket, in the bedroom.”

To help contact tracers catch up with their heavy call volumes, Alberta Health introduced new procedures in mid-November. Now, AHS directly notifies close contacts of COVID-19 cases with a focus on three priority groups: healthcare workers; minors (parents will still be notified by AHS if their child is exposed at school); and individuals who live or work within congregate or communal facilities.

Albertans outside of these priority groups, who have tested positive for COVID-19, are asked to identify their own close contacts of the exposure. They must self-isolate, complete the COVID-19 Close Contacts Identification Guide and enter their close contacts into the COVID-19 Contact Tracing Tool.

Greeno and Lavorato’s workload may have eased with the new protocol, but the work itself isn’t always easy.

Contact tracers have voiced frustration over a growing number of people who refuse to disclose who they’ve been with or where they’ve been while infectious — a decision that’s guaranteed to prolong community spread. Staff have also been yelled at and hung up on by folks who are angry, afraid and suspicious, and they’ve navigated through many a language barrier.

“I remember being on a call where we were using a translator,” adds Greeno, “and as we were speaking with the individual, I could hear the voices of many others in the background. I realized our conversation was being repeated to all these people who were there. Being in the same room made them all close contacts and I knew that we’d need to have a conversation with every person there. It took hours.”

Greeno says she learns so much about the people she calls, and afterwards can’t help but wonder how they’re doing.

“You really take a piece of each family with you after all these investigations,” she says, “You know they have to stay at home. You’ve asked if they have somebody they can call to get them groceries and supplies, or pick up their medication, or help if they have a medical emergency. You know who their family members are.”

When confirmed cases are anxious to return to work, Lavorato and members of the surveillance team are mindful to check back with them, as isolation comes to an end, to clear them as soon as it’s safe. Some of them, however, have refused to cooperate, saying they’re afraid of losing their jobs.

Dr. Deena Hinshaw, Alberta’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, says that while she understands people are tired of COVID-19 and how it’s disrupting their lives, choosing not to work with contact tracers only worsens the situation.

"If you are diagnosed with COVID-19, please don't turn any understandable anger against the contact tracers, who are doing their job as part of a collective effort to maintain manageable levels of transmission," Dr. Hinshaw said in a Twitter post.

“The message I really try to give them is, ‘you have done nothing wrong’. We just want to make sure everybody is safe, and keep others around you safe.’ I really try to be kind. Sometimes people cry,” says Greeno.

“I listen to their story about financial concerns, and that’s been a common thread. They’ll try to figure out how they can still work even though they’re sick. They say things like ‘what if I stay in my truck and just tell the others what to do?’ And some are so sick they feel like they’re going to die. They have kids. It’s tough.”

When she’s asked why people should co-operate with contact tracers — or reach out to their own contacts when asked to — Lavorato’s answer is simple: “First and foremost, because we all want this to end. Why indeed? So people can attend their graduation. Couples can get married with their families present. People can visit loved ones again in long-term care. Go to work and school. And avoid a lockdown leading to a loss of local business.”

Both women say their challenging days are lightened by a supportive leadership team, the involvement of the office of the Medical Officer of Health and the team in Environmental Public Health.

“I am humbled every day by the individuals involved in this COVID-19 case investigation work,” says Cheryl Andres, South Zone Director of Chronic Disease Management and Primary Health Care. “Their work and home lives have changed as a result of the virus and the reality of that is on their faces every day, with every phone call they make.

“Their dedication to keeping our population safe and well is beyond anything I have seen before and, despite the challenges, they continue to do this work. I am grateful every day for them. This virus is no one’s fault. We all just need to be kind and find ways to work together to look after one another in the midst of it. This staff is the epitome of that.”

Greeno adds: “I find it very interesting and fulfilling work, I really do. And for the most part, people are very thankful for what we're doing.”