November 19, 2014

Story by Gregory Harris; photo by Colin Zak

From the time he was diagnosed with depression at age 11, Jared spent much of his life just trying to cope with mental illness.

“I was constantly seeing psychiatrists and doctors for treatment,” he says. “I was hospitalized several times for suicidal thoughts. I was quite disabled – my whole life was just managing my depression.”

Jared tried most of the standard therapies, including anti-depressants and counselling, but he was still unable to work or have much of a social life.

Now 28, his life has turned around thanks to an experimental treatment that’s showing promising results in a research study at Alberta Health Services’ Foothills Medical Centre.

Called deep brain stimulation (DBS), the therapy involves surgically implanting electrodes to deliver impulses to the brain.

“Deep brain stimulation has been effective in helping control tremors due to Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders, but there has been little research to evaluate its effectiveness in people with treatment-resistant depression,” says Dr. Zelma Kiss, an AHS neurosurgeon and co-principal investigator in the study.

“Deep brain stimulation has been effective in helping control tremors due to Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders, but there has been little research to evaluate its effectiveness in people with treatment-resistant depression,” says Dr. Zelma Kiss, an AHS neurosurgeon and co-principal investigator in the study.

“It doesn’t work for everyone but, for those who do see benefits, the improvements can be quite remarkable,” says Dr. Kiss, also an associate professor in the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine.

For Jared, the difference has been like night and day since his surgery in January 2014.

“I’m working full time, I go out socially, and I can think clearly,” he says. “Before, I felt defined by my depression; now, I can be me again.”

Early research indicates about one-in-two people undergoing DBS will experience at least a 50 per cent decrease in the severity of depression. Within that group, depression will almost disappear in half of those people.

Calgary researchers are particularly interested in pinpointing the optimal levels of stimulation to improve the therapy’s effectiveness.

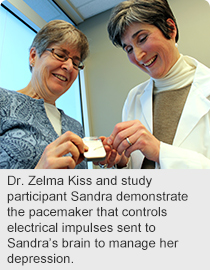

Study participants undergo a six- to eight-hour neurosurgery in which brain activity is analysed to determine the optimal location for implanting the electrodes. Then, a few days later, the patient has a second operation to insert a brain pacemaker under the skin of the chest to control the electricity delivered to the electrodes.

To date, four patients have been enrolled in the study; researchers are still looking for another 20 to take part. To be eligible, patients must have tried all other therapies for depression, such as at least four classes of anti-depressants, cognitive behavioural therapy, psychotherapy, electroconvulsive shock therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation.

“Usually the people eligible for deep brain stimulation will have suffered from major depression for decades,” says AHS psychiatrist Dr. Raj Ramasubbu, co-principal investigator in the study.

“Usually the people eligible for deep brain stimulation will have suffered from major depression for decades,” says AHS psychiatrist Dr. Raj Ramasubbu, co-principal investigator in the study.

“Often their depression is so debilitating that it affects every aspect of their lives. Family relationships suffer, work becomes impossible, and their overall quality of life is very poor,” says Dr. Ramasubbu, an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry.

Another study participant, Sandra, has also felt better since beginning DBS therapy three years ago, although her improvement hasn’t been quite as dramatic as Jared’s.

“I still take a lot of medication and I wouldn’t say that I’m cured, but it’s a whole lot better than it was,” she says. “I cope better with everyday life. And my husband doesn’t worry about leaving me alone as he once did.”

It’s estimated about one per cent of the population have treatment-resistant depression – about 10,000 people in Calgary.

For more information about the study, contact the study co-ordinator at 403-210-6905.

The study is based out of the U of C’s Hotchkiss Brain Institute and Mathison Centre for Mental Health Research and Education and is funded by Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions.