May 30, 2019

‘It’s nice to know there are protocols in place for us that live so far from major centres.’ Diane Therriault, wife of stroke patient André Therriault.

Story by Kit Poole

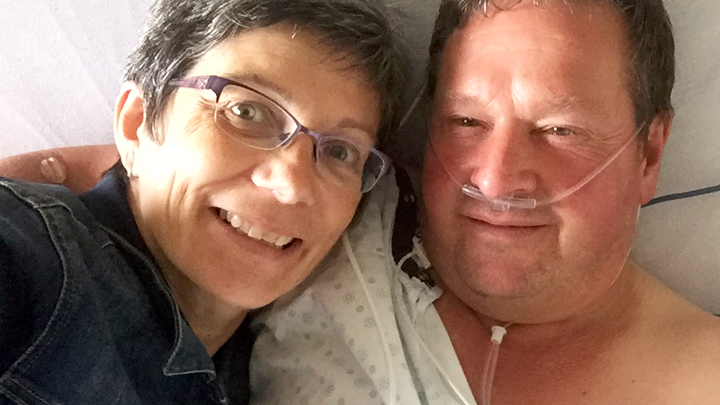

As André Therriault lay in hospital two years ago after having a stroke, he thought, “Will I be in a bed for the rest of my life?”

But after just five days, he was on his way home to his 6,800-acre grain farm in Donnelly, south of Peace River, and credits the streamlined care Alberta Health Services (AHS) has in place for rural stroke patients.

“It was phenomenal the care that I got,” says the 59-year-old father of four. “I don’t quite have the energy and have a bit of memory loss. But 95 per cent of it is back to normal.”

Therriault’s story began in 2017 at the beginning of harvest season, when he became dizzy while working in his garage. His son could see his father’s face had begun to droop, suspected he was having a stroke and called for an ambulance to transport him to the Peace River Health Centre, 65 km away.

That set in motion AHS’ stroke program, whereby emergency department doctors are linked via teleconferencing for immediate consultation with a stroke neurologist. The neurologist — in this case, Dr. Brian Buck — was able to see the computed tomography (CT) scan remotely from Edmonton’s University of Alberta Hospital (UAH).

“I was able to identify that, from the description I got from the ER physician, he was suffering from a stroke,” Dr. Buck says. “And from the CT and CT angiogram, I was able to see that one of the main arteries from the back part of his brain was almost entirely blocked off.”

Therriault had an ischemic stroke, which is caused by a sudden blockage of an artery to the brain, depriving it of critical nutrients, such as glucose and oxygen. This can cause brain cells to die, affecting parts of the body controlled by that area of the brain. If the damage is severe, it can cause death.

Dr. Buck ordered that Therriault be given the clot-busting drug tPA (tissue Plasminogen Activator).

Soon after, Therriault’s wife Diane says his symptoms began to abate, and he was medevaced from Peace River to the UAH for further observation.

“The nurse before we left, she could see that André was very upset and scared, so she took him and said, ‘Don’t worry. You are not going to die today,’ ” Diane says.

The nurse was right.

“His brain rewired somehow and his farming business is still top-notch,” Diane says of her husband. “He’s able to do all his business deals and he does his own bookwork.”

Dr. Buck says the speed of treatment was key to Therriault’s recovery and credits the initiatives created through AHS’ Cardiovascular Health and Stroke Strategic Clinical Network.

“We’ve worked over the past several years on creating an integrated network right from the pre-hospital stage to the emergency room and beyond to ensure that rural stroke patients have as close as possible access to the same care as someone who is having their stroke across the road across the road from a hospital,” he says.

It has also meant the average time between stroke diagnosis treatment with the clot-busting drug has been reduced by half from 70 minutes to 40 minutes.

For Therriault, the result is his health has recovered and life with his family has changed — for the better.

“I’ve slowed down quite a bit on the working side of it. I take care of my health,” he says. “I take more weekends and we spend more time together.”

Adds Diane: “It’s nice to know there are protocols in place for us that live so far from major centres.”