June 23, 2020

Despite lingering pain, Kevin Iwaasa has returned to mountain biking after an accident that nearly left him paralyzed.

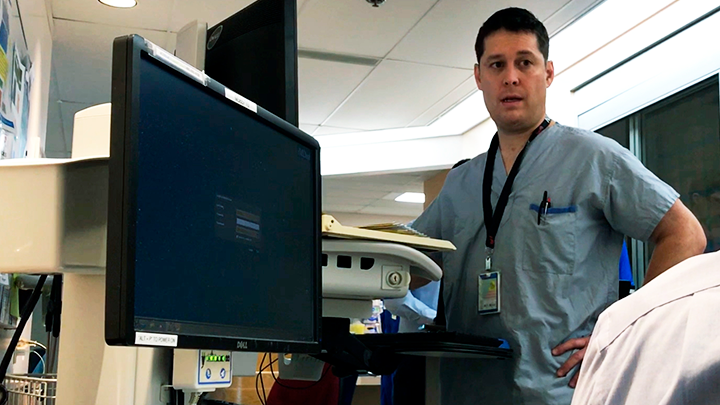

After a serious spinal injury, nurse Kevin Iwaasa has returned to work in Chinook Regional Hospital’s ICU with a new understanding of what patients experience and how he can make a positive difference.

Story & Photos by Patrick Burles

His ordeal began on a warm July evening in 2017 when Iwaasa — a critical care assistant head nurse for Alberta Health Services (AHS) at Chinook Regional Hospital (CRH) — ventured out with friends for some mountain biking on a trail near Crowsnest Pass. The plan had been to ride, go out for dinner and then head home.

“That was the plan,” says Iwaasa, who adds with a smile, “However, I ruined that.”

Iwaasa misjudged his speed as he reached the top of a jump. He rotated in the air and crashed to the ground head-first. His bike landed on top of him.

“It’s not the first time I’ve crashed or fallen down. Usually I just say, ‘Oh, I’m good, I can get up.’ But as soon as I hit, I must have had some intuition.”

After a grueling journey through the woods on a spine-board and a quick stop at the hospital where he worked, he was taken to Foothills Hospital in Calgary. That’s where a CT scan revealed a fractured spine, an injury that doctors say came close to severing the spinal cord entirely. He needed surgery — and there was no guarantee he would ever walk again.

“Basically, they said there was a high likelihood that I could be paralyzed,” says Iwaasa. “But when you see the fracture, there’s no other option. The area I work in, we gotta do what we gotta do, so let’s just get ’er done.”

The surgery proved successful — bit it was merely the first step on Iwaasa’s path to recovery.

“I spent 10 days recovering in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) which, for an ICU nurse, is my worst nightmare,” he adds with a chuckle.

“But it was actually very good; I tell people all the time the experience was really positive for me. It made me a better nurse, made me understand some of the directions we’re taking AHS — patient-and family-centred care, the priorities and how it made a difference in my stay.”

After experiencing life in hospital from literally a new perspective, Iwaasa began to appreciate the importance of being ‘connected’ to those supporting him — which is the number-one goal of the AHS CoACT program — designed to drive collaborative care and develop a culture in which healthcare professionals work with patients and families.

Practices include holding patient rounds at the patient’s bedside, regular check-ins on a patient’s comfort that can range from a pain assessment to making sure a book is within reach well as providing a whiteboard to share information and ensuring staff always introduce themselves and their role when they enter a room.

When discussing what mattered to him as a patient, Iwaasa singled out the check-ins and introductions. Being forced to lay flat on his back, and in a constant fog created by medication and a concussion, he adds that the emphasis on human interaction helped tether him to the world and reduced his sense of isolation.

Ironically, he also became a fan of the whiteboards during his time as a patient, something he admits he didn’t always appreciate before his injury.

“I was a naysayer when (whiteboards) first came out. I’d been nursing 20 years and we were fine without them,” says Iwaasa. “But as a patient, I loved my whiteboard. When I was coming out of my delirium and was confused, I looked at my whiteboard all the time to figure out what was going on.”

Jaime, Iwaasa’s wife, adds the bedside patient updates stood out as an important part of getting through their traumatic experience.

“In the intensive care unit, there was a team of all the different specialized individuals who gathered for rounds every morning,” she says. “I was there to hear his update and also plan for the day and the days to come. That really helped take some of the stress away, just knowing what to expect. It was a chance to ask questions — and it makes you feel at ease — knowing you’re part of the process.

“For them, and for everybody else involved in Kevin’s care, doing this day-in and day-out, it may not mean a whole lot. But for the people going through such a stressful time, it meant everything,” she says. “I’m so grateful for them every day.”

It’s now Iwaasa’s hope that his life-changing experience can benefit his colleagues, and in turn, their patients. He’s delivered presentations to his colleagues at CRH and to trauma teams in Calgary, sharing his story as a way to reinforce that they’re on the right track.

Ever the optimist, he says that the lingering pain in one arm and his back is a constant reminder, not of what went wrong, but of everything that went right. It now reminds him of why he became a nurse — and that no matter how long he’s in the profession, there will always be room to grow.